What is Dupuytren’s Disease?

Also called Dupuytren’s contracture, this is a common condition caused by thickening of the tissue directly beneath the skin in the hand. This layer of tissue is called the ‘palmar fascia‘.

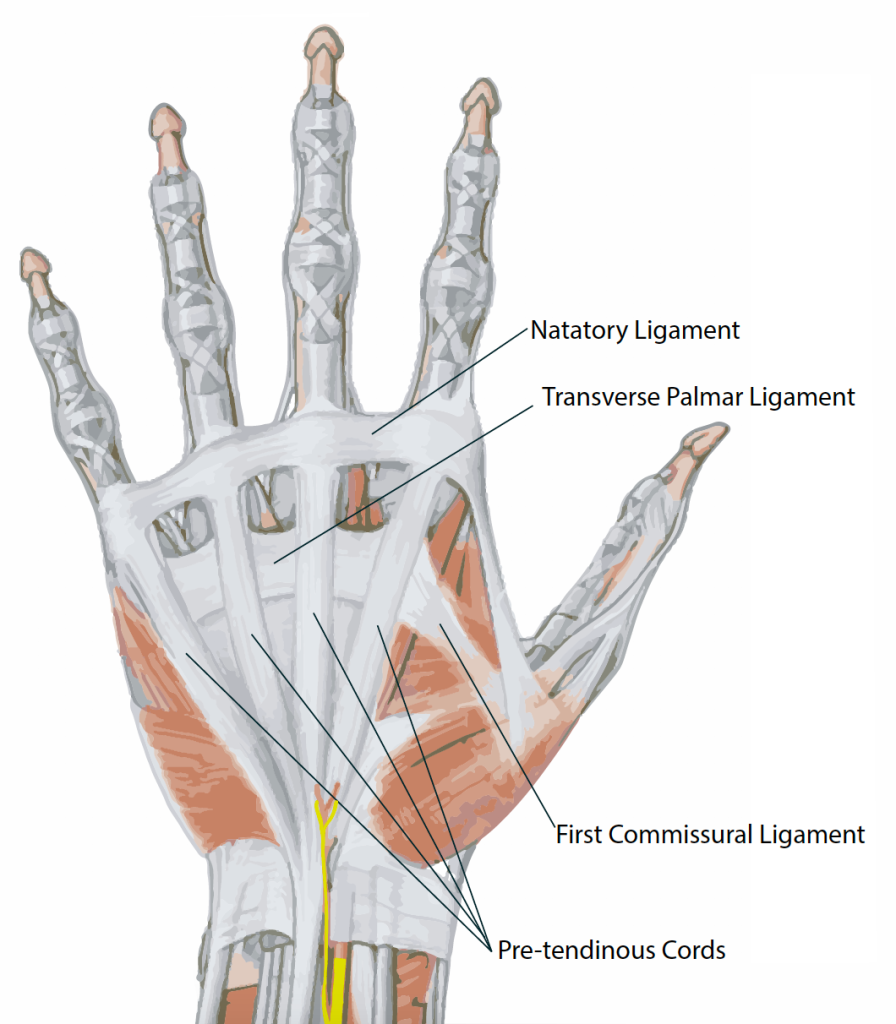

Palmar fascia is a tough fibrous tissue which binds the skin of the palm to the underlying skeleton to make is secure. The skin on the back of the hand and over most of the body is very mobile, but the palm and fingers are used to grip, and if the skin were mobile in the palm, grip would not be stable. Fascia makes this grip stable, and also protects the small nerves and arteries in the palm from trauma.

In Dupuytren’s disease, a type of scar tissue forms in the fascia. Scar tissue contracts with time – anyone who has had a cut in skin will know that although this initially looks big, with time the scar matures and shrinks down. In the same way, the scar tissue that forms in Dupuytren’s disease contracts down, and this unfortunately causes what we call contracture, or an inability to straighten a joint.

Early Dupuytren’s disease is characterised by firm nodules in the palm, but as the condition progresses, the fingers start to develop contracture.

Why does it develop?

Dupuytren’s disease is a genetic condition, common in Northern Europe. The genetics are not simple, and although many people know of a relative with the condition, this is not always the case.

It may be associated with diabetes, smoking, alcohol or previous trauma, but most affected people have none of these associations. It does not seem to be strongly associated with manual work.

What are the symptoms and how does it develop?

The first sign of the condition is often a nodule or lump in the palm of the hand, which can often be painful in the initial stages. As well as this lump, skin ‘pits‘ may develop, where parts of the skin are pulled down into the palm.

As the condition progresses, a cord may become evident. This is often mistaken for a tendon, but in fact the tendons are not involved in this condition. Patients with moderate or severe Dupuytren’s may have extensive diffuse lumps in the palm, fingers and occasionally the thumb.

Can it occur elsewhere?

Yes, sometimes it can occur in other parts of the body where it is known by different names:

- Soles of feet – Ledderhose disease. This may produce lumps on the sole of the foot, particularly under the arch of the foot.

- Over the knuckles – Garrod’s pads.

- In men, it can affect the penis – Peyronie’s disease.

When do I need treatment?

Dupuytren’s disease is not a serious problem. It is NOT a type of cancer. It may affect up to 2 million people in the UK, but only a small amount of people require surgery.

Many people do not find that the condition affects their function, and do not require treatment. If you are able to get your hand flat on the table, none of the treatment options outlined below are likely to be of any benefit to you. However, if the contracture is beginning to interfere with the function of your hand, for example having problems putting your had in a pocket or glove, or holding tools, then discussion with a specialist may be a good option.

For patients with painful nodules in the palm the pain will normally settle with no intervention. Surgery is a known trigger for disease progression and therefore doing an operation can make things worse at this stage.

What are the treatment options?

Conservative Management: If the condition is not particularly bothersome, it is quite safe to leave things as they are. Many people have fairly stable disease that does not change much over the years, and never seek help with the condition. In others, the disease progresses rapidly, such that the joints become contracted over the course of 6-12 months, but this is relatively unusual.

Stretching out the hands may be useful, although there is no strong evidence that this prevents contracture. This can be done easily by pushing the fingers of each hand against each other regularly.

Procedures:

These may be considered if:

– There is a contracture that is interfering with the function of your hand.

– Your condition is progressing relatively rapidly and, if left longer, would require more major surgery to address it.

– There is recurrence of the condition that is interfering with hand function.

There are several different procedures available which we describe below. The two most common and well established treatments for people with newly diagnosed dupuytren’s disease, are needle fasciotomy and limited fasciectomy.

Needle fasciotomy:

This is a performed in the outpatient clinic. You must NOT drive yourself to and from your appointment. We inject a small amount of local anaesthetic to numb the skin and this allows the surgeon to divide the Dupuytren’s cord at multiple levels with a needle through the skin. This technique is not suitable for every patient, it depends on the characteristics of your Dupuytren’s tissue.

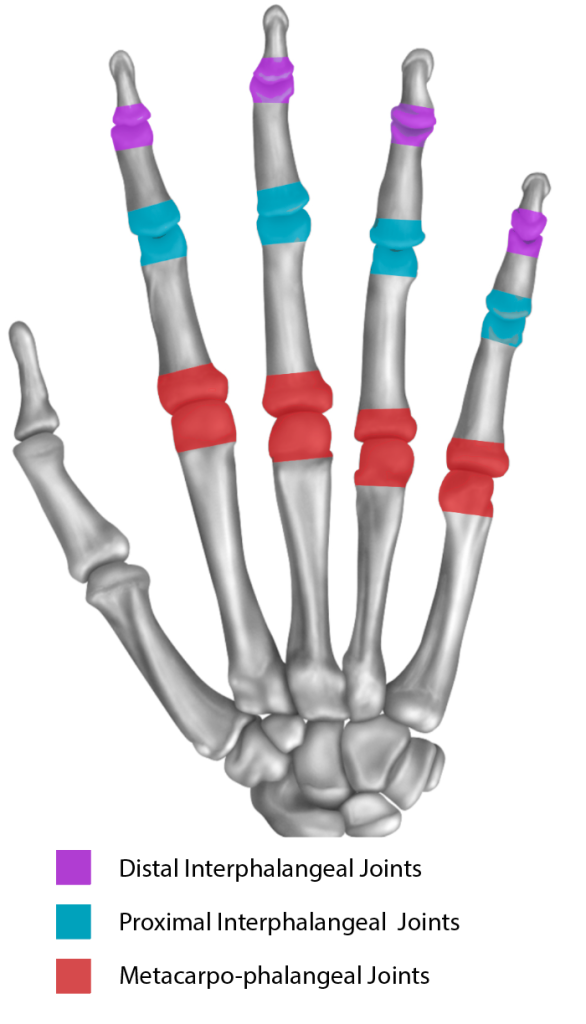

The contracture usually improves, but may not come fully straight especially if the contracture affects the finger joint (PIPJ in blue) rather than the knuckle (MCPJ in red).

This option does not normally require time off work, and recovery is very quick. Like all procedures, there is a small risk involved with needle fasciotomy, but most patients report high satisfaction levels at 1 year. There is thought to be a quicker recurrence rate with this procedure compared to the open procedures described below.

After your procedure you will be taken to the hand physiotherapy department. The physiotherapist will show you some hand stretching exercises and make you a splint to wear at night time only for 6 months.

Limited Fasciectomy:

This normally involves a regional anaesthetic where the anaesthetist numbs your whole arm. The surgeon will make an incision along the length of the finger, to allow the entire cord to be removed safely. Part of the palm wound may be left open, and this can take around 4 weeks to heal. Most patients are able to get home the same day.

Post-operatively you may require input from various members of our team:

Nurses: You will be seen by the nurses to trim or remove your stitches. It is quite common for the wound to appear macerated but this is normal.

Hand Physiotherapists: An appointment will be made with our hand physiotherapy team 5-7 days after your operation. Here wound care and stretching exercises will be explained and you will be fitted for a splint to be worn at night time only for 6 months. It is important to start moving your hand as soon as your dressings are removed in clinic.

Dermofasciectomy:

Under regional anaesthetic, the cord is removed together with the overlying skin. The skin is replaced with a graft (when a healthy piece of skin is taken from another part of the body, usually the forearm). This procedure is undertaken for recurrent disease, or for extensive disease in a younger individual. A plaster cast is required for the first 7-10 days after surgery and the palm wound is sometimes kept open, again requiring about 4 weeks to heal.

Amputation:

Amputation of the finger may be an option in very severe or recurrent Dupuytren’s in the finger. This is very much the last resort, but can improve function with severe cases where the above procedures are not appropriate.

Alternative Treatments:

Steroid injections: These injections may help with local tenderness, but have no significant effect on the disease and are not recommended.

Xiapex injection: This drug has now been withdrawn from the market.

Radiotherapy: Radiotherapy is an experimental treatment offered in some research centres, but is not available on the NHS in Scotland

© Aberdeen Hand Service 2021